Last Updated on March 19, 2022 by Aenia Amin

“…it could be worse. Consider the plight of veterinarians. The average tuition and expenses for a veterinary degree at a private school has doubled in the last 10 years…yet their pay remains moribund…”

–Steven M. Davidoff, “The Economics of Law School.”1

Overview

The veterinary profession is currently suffering the effects of decades of decisions based on unexamined beliefs and subjective surveys rather than objective, statistically valid evidence. With respect to workforce needs and career opportunities, we are operating in the dark. There are signs of potential improvement, most notably the 2013 AVMA-IHS Veterinary Workforce Study. We must improve qualitatively, though, if we are to better the economic condition of our profession – which we must do to maintain the quality of service we provide to society.

Over a series of posts, we will show some effects of policy decisions made in the absence of sound data. We will identify areas where we can improve our profession’s prospects by compiling and analyzing high-quality data across the entire profession. The series consists of:

- Meet the Pink Elephant in the Room: Gender in Veterinary Medicine – 5/2/13; PDF

- Meeting Ourselves, Coming and Going: Maldistribution – 5/13/13; PDF

- Meet Big Veterinary: How the AAVMC Could Serve Students Better – 5/17/13; PDF

- Meet Big Veterinary: How the AVMA Could Serve Its Members Better – 5/22/13; PDF

- Meet Big Ed: Schooling Veterinarians is Big Business – 6/12/13; PDF

Meet the Pink Elephant in the Room

Although the practitioner population in the US has swelled hugely over the past two decades, we have service gaps in public health, food security, animal welfare, and wildlife health. Meanwhile, companion animal private practice is saturated beyond economic sustainability. If we had comprehensive, current data about how individual veterinarians respond to socioeconomic changes, we could better predict the response of the veterinary workforce to those changes. Without this, we will continue to risk such gaps and bulges.

With the growth in the practitioner population came a dramatic gender shift.2,3 The National Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners (NBVME) administers the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination (NAVLE). According to NAVLE Technical Reports,4 40,184 people have passed the NAVLE since 2001. While NBVME tests administered from 1993 to 2000 were not computerized and thus can’t be examined with the same degree of precision, applying similar rates of passage as achieved on the NAVLE yields an approximate period total of 60,349 people entering practice between 1993 and 2012.a

The proportion of female DVM recipients documented in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) has been over 50% for more than 20 years and now stands at almost 90%. If the same gender percentage applies to those passing the NBVME exam, then the profession gained approximately 43,028 female practitioners in the past twenty years. We have precious little data documenting the behavior of these members of the veterinary workforce.5,6

Conventional wisdom holds that women work part-time or intermittently to accommodate a family. Such workers can contribute elasticity to a labor force by being able to work more if demand goes up. If true, the large percentage of recent graduates that are female could dampen upward compensation trends for decades.

We need objective, current data on the workforce participation patterns of male and female DVMs. We need to know the number and distribution of hours worked by each, as well as the perception each has of the hours they work. Are female DVMs more likely to work fewer hours? Does this depend on having children? Are the hours worked by female DVMs more likely to occur at different times, such as evening and weekend hours, overnight shifts, or in concentrated blocks indicating relief work? How do the genders differ in the number and distribution of hours worked as careers and families progress?

|

Why are so many recent applicants and therefore graduates female? We don’t know. (We don’t even know how many graduates there have been.) The above figures contain numbers that had to be inferred or approximated. Neither the programs conferring the degree, the entity responsible for program quality (Council on Education, COE) nor the professional organization representing such programs (Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, AAVMC), make comprehensive applicant or graduate numbers readily available. We have effectively no system for tracking how many total graduates there are, what schools they attended or what their education cost – much less where they live and work, how they spend their professional time, and how much they get paid.

In the time that it has taken to sit down and compose this series of essays, both the AAVMC and AVMA have released subjective datasets documenting the employment of recent graduates and gaging the workforce as a whole. We flatter ourselves that we have distributed the thinking and the resulting information compiled here to many of the WAG, the executive Board, AVMA staff and other organizational leaders, and influencers in the profession at strategic points in time over the past two years. We applaud those two associations for conducting their respective surveys, and to the extent, the data they accumulated is objective and useful for real-world ground-level decision making, they should be encouraged to continue to take similar steps moving forward.

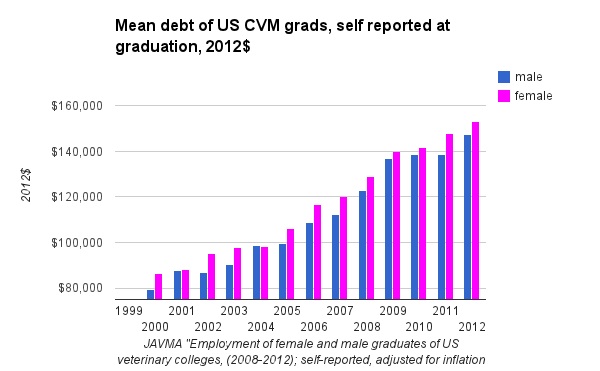

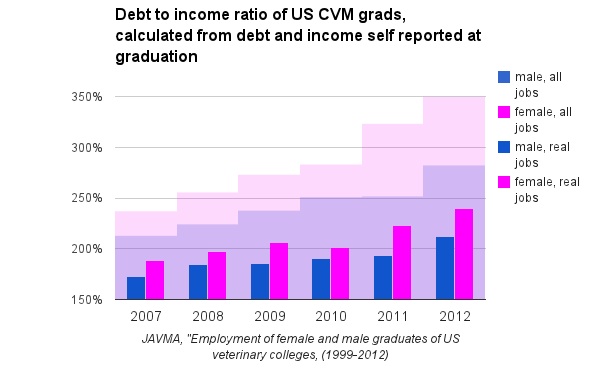

We are going to need more. A LOT more. These datasets, while timely, barely begin to address our data needs. They in fact may even be worse than nothing, as we fool ourselves into thinking that what we have is what we need since we spent a lot of time, effort, and money to get it. We do know many women report graduating with more debt than men, yet receiving lower pay.

|

This discrepancy in compensation appears to persist regardless of ownership status or time since graduation. As long as the largely female veterinary labor pool continues to experience gender disparity in debt and compensation as shown above and elsewhere,7 gender disparities in ownership will likely persist as well.

Much of the data needed is generated annually by individual organizations such as the AAVMC, COE, and state licensure boards. However, those organizations do not coordinate or share their data. The much anticipated 2012 National Academies of Science workforce study was delayed because of this:

The report has been long in the making, in part because of the inconsistent ways in which organized veterinary medicine compiles data, rendering it difficult to analyze long-term trends in the profession.8

The AAVMC compiles the annual Comparative Data Report and the Veterinary Medical College Application Service (VMCAS) database.9 The COE holds accreditation reports while the American Association of Veterinary State Boards (AAVSB) has access to the numbers and geographic distribution of licensees in every state.

Licensee information is a matter of public record. The individual state boards already collect, maintain, and disseminate this information. The AAVSB could facilitate the construction of a common platform for housing, analyzing, and sharing aggregated information. This would let us know where our gaps were, geographically and demographically. Thus in addition to serving their own mandate to their individual states, the boards could contribute to fulfilling the profession’s mandate to serve society as a whole.

|

Another rich source of data about veterinary applicants, students, and graduates is accreditation reports. Accreditation, the voluntary process of quality assurance in what is taught at a school, is coming under pressure in all of US higher education to be more transparent. Some veterinary schools already make their COE accreditation self-studies available, either within the college community by placing copies in the library or more widely by placing the studies on the internet. The largest accreditor in the country, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges, announced last year that it would make accreditation reports public, and accreditors in other fields are expected to follow suit. From the April 2012 Report to the Secretary of Education:

…data collected for accreditation by accrediting agencies should be available to the public by both the institution and the accrediting agency…to afford students and the general public the opportunity to make accurate comparisons based on facts. …Make accreditation reports about institutions available to the public.10

The increased national emphasis on transparency declared above was expressed by the requirements COE received in December 2012 in their review before the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI). The COE anticipates easily fulfilling those requirements by the next anticipated review date.d

The National Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners (NBVME) publishes an annual comprehensive report on the North American Veterinary Licensing Exam, releasing far more of the objective information that it produces than any other organization listed here. It is this wealth of information that allows the projection of supply and demand of veterinarians found in the final installment of this series.

Notwithstanding the availability of various statistically inadequate data, we don’t know what we need to know to make data-driven decisions about our own profession. The lack of basic, objective demographic and economic data about the individual members of our profession – who does what, when and where, for how much – means we can’t understand and predict veterinary workforce behavior. A major contributing factor to this is the inability or unwillingness of veterinary medicine’s professional organizations to coordinate and share their information.

Let there be no misunderstanding. The economic problems that our profession faces are not caused by a female-dominated workforce, any more than they are caused by the accreditation of new schools. It seems that whenever the topic of gender is raised, a perception of blame follows.11 There is no blame to be assigned, just understanding to be sought. Despite repeated costly attempts that leadership believes show otherwise, no one is yet in a position to accurately capture and analyze this trend or emerging trends. This lack of analytical ability handicaps the profession’s response-ability.

Footnotes

(a) Boyce, J. Personal email communication with Myers, E. 22 June 2011. Boyce is the Executive Director of the National Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners.

(b) Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Institute of Education Sciences. “Degrees conferred by degree-granting institutions in selected professional fields, by gender of student, control of institution, and field of study: Selected years, 1985-86 through 2009-10.” Custom query by Myers, E. Available at:

(c) McCormick, DF. Telephone interview with Gates, RG. 7 Nov 2012. McCormick is a Charter Member of Association of Veterinary Practice Management Consultants and Advisors (AVPMCA) and is currently the Immediate Past President.

(d) Granstrom, Dave. Personal communication with Myers, E. at AVMA Veterinary Leadership Conference. 4 Jan 2013.

References

(1) Davidoff, SM. “The Economics of Law School.” Deal B%k, 24 September 2012. Web. Accessed: 11/13/2012. Available at: <http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/09/24/the-economics-of-law-school/>

(2) Shepherd, AJ. (2010). “Distribution of actively employed US veterinarians by state and gender, 2003-2008.” J Am Vet Med Assoc, 2010; 236:420-422.

(3) Wise, JK; Shepherd AJ. “Employment and age of male and female AVMA members, 2003.” J Am Vet Med Assoc, 2004; 225:876-877.

(4) National Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners. NAVLE® Technical Reports. Updated 28 August 2012. Accessed: 12/1/2012. Available at: <http://www.nbvme.org/?id=82&page=NAVLE+Reports>

(5) Smith, C. “The Gender Shift in Vet Med: Cause and Effect.” Veterinary Clinics of North America – Small Animal Practice. Saunders, 2006 March;36:329-339.

(6) Smith, C. “Gender and work: what veterinarians can learn from research about women, men, and work.” J Am Vet Med Assoc, 2002;220:1304-1311.

(7) Felsted, Karen E., DVM, CPA, MS, CVPM; Volk, John. “Why Do Women Earn Less?” Veterinary Economics, 2000; 41:33-38.

(8) Committee to Assess the Current and Future Workforce Needs in Veterinary Medicine; Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources; Board on Higher Education and Workforce; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Policy and Global Affairs. “Workforce Needs In Veterinary Medicine.” National Academies Press, Summer 2012. Web. Accessed: 1/13/2013. Available at: <http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13413>

(9) AAVMC Annual Data Report. 2011-2012. Web. Accessed: 1/13/2013. Available at: <http://www.aavmc.org/Public-Data/Annual-Data-Report.aspx>

(10) U.S. Department of Education National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity. “Higher Education Act Reauthorization, Accreditation Policy Recommendations.” Web. April 2012. Accessed 3/1/13. Available at: <http://www.msche.org/documents/naciqi-final-report.pdf>

(11) Lee, J.A. DVM, DACVECC, DABT. “Are We Abandoning Our New Graduates?” Web. Accessed: 4/26/2013. Available at: <http://veterinaryteambrief.com/article/are-we-abandoning-our-new-graduates-3> In particular, Dr. Lee’s statement, “Here is where I feel some of the problems lie: … An all-female field. I’m all for women’s equality, but a woman-dominated veterinary field will have repercussions.”