Last Updated on June 27, 2022 by Laura Turner

Mark Twain “The physician who knows only medicine, knows not even medicine.”

Ahhh, spring! A time to shake off winter cobwebs and cabin fever, a season for rejuvenation, long walks in the park, hooking up with friends and family, falling in love, etc. Well, this may be so for “normal” folks, but not for those poor souls who have voluntarily submitted themselves to the unimaginable workload of medical school or pre-health education! Spring for many students just means more seemingly unending psychological and physiological stress. Things such as MCAT, USMLE, COMLEX, DAT, PCAT and, yes, those pesky applications and letters of recommendations around the corner at the end of spring are all things student can look forward to (not to intentionally add more stress). Medical and pre-health students know from experience that this relentless stress can and often does wreak havoc on their body, mind and spirit. It does not come as a surprise that these experiences can result in anxiety disorders, chronic fatigue, depression, and immune deficiency. Students suffer from perpetual fight or flight sensations, as if being chased by a tiger, symptoms which escalate around exams, applications, or interviews.

So much for stating the obvious. The more important question is what to do about it. How can a medical student be healthy and strong, even improve performance while progressing through medical school with a greater sense of ease and well-being? What would a personal stress intervention plan have to look like in order to be helpful, relevant and useful? What would it take for students to give such a plan a second look and incorporate helpful strategies into their day to day of too-much-to-do-and-too-little-time?

For a number of years, as academic counselor and Director of the Office of Learning Enhancement and Academic Development (LEAD) at Western University of Health Sciences, I have been able to assist hundreds of medical students with stress managing strategies that are simple to integrate and habituate, even when confronted with a super busy schedule.

A definition of stress: “Stress is anything in the external world that knocks you out of homeostatic balance,” Robert Sapolsky, Professor of Neurology at Standford.

During experience of stress, cortisol and noradrenalin flood the prefrontal cortex. This area in the brain controls working memory, where information is processed and retained. Result: stress reaction impacts the ability to take in, understand and retrieve information.

In all relaxation strategies, an attitude of unconditional friendliness is being practiced. If this is too much in the beginning, the cultivation of a curious and non-judging attitude is a helpful key toward success.

Simple stress managing strategies, practiced persistently, connect (the practitioner) with the body, the ”felt sense” of an otherwise automatic response. This awareness activates the physiological process to soften and release of tension, releasing the hold on cognitive process. The result: we connect with the ability to choose the most constructive response to any situation, feeling, and thought in real time. At its core, these strategies allow for the cultivation of the Emotional Intelligence skill set, self-regulation, internal motivation, empathy and social skills.

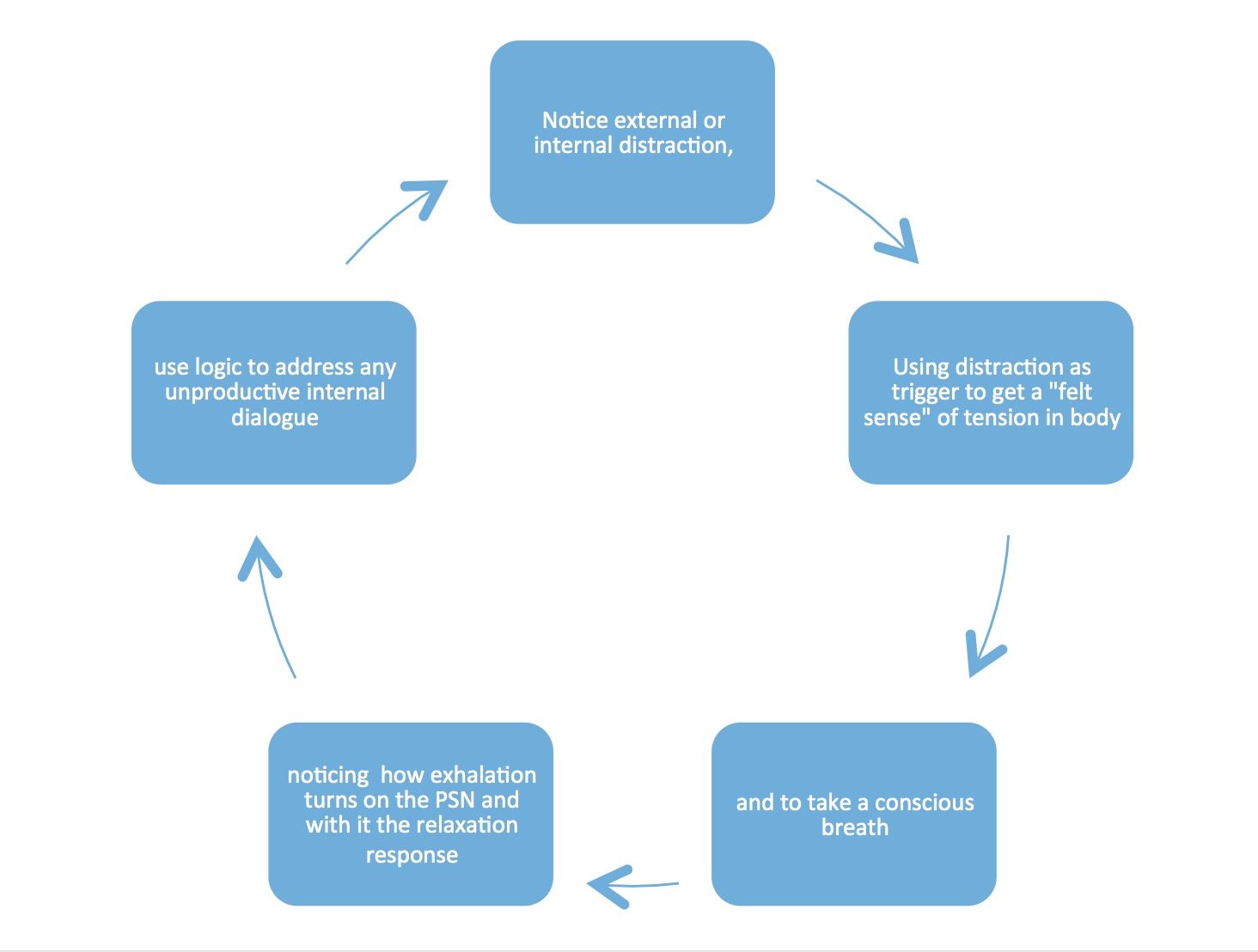

The diagram below describes a re-directing strategy in which the breath is used to neutralize distractions to soften and release stress reactions they may have triggered. This process is activated when, counterintuitively, the practitioner makes the choice to lean toward the discomfort causing distraction, letting go of the need to contract in defense. The consciously observed somatic process (of breathing) makes it possible to relax around distractions, such as the perpetually negative and intrusive dialogue of the internal critic. With this practice, the PNS is consciously activated and the resulting release of tension is used as felt sense focus, cutting off the self-identification with distractions such as a negative thought process. Success lies in the habituation of this process. Once tension is released, unproductive thought processes can be deconstructed and re-directed toward more useful thoughts.

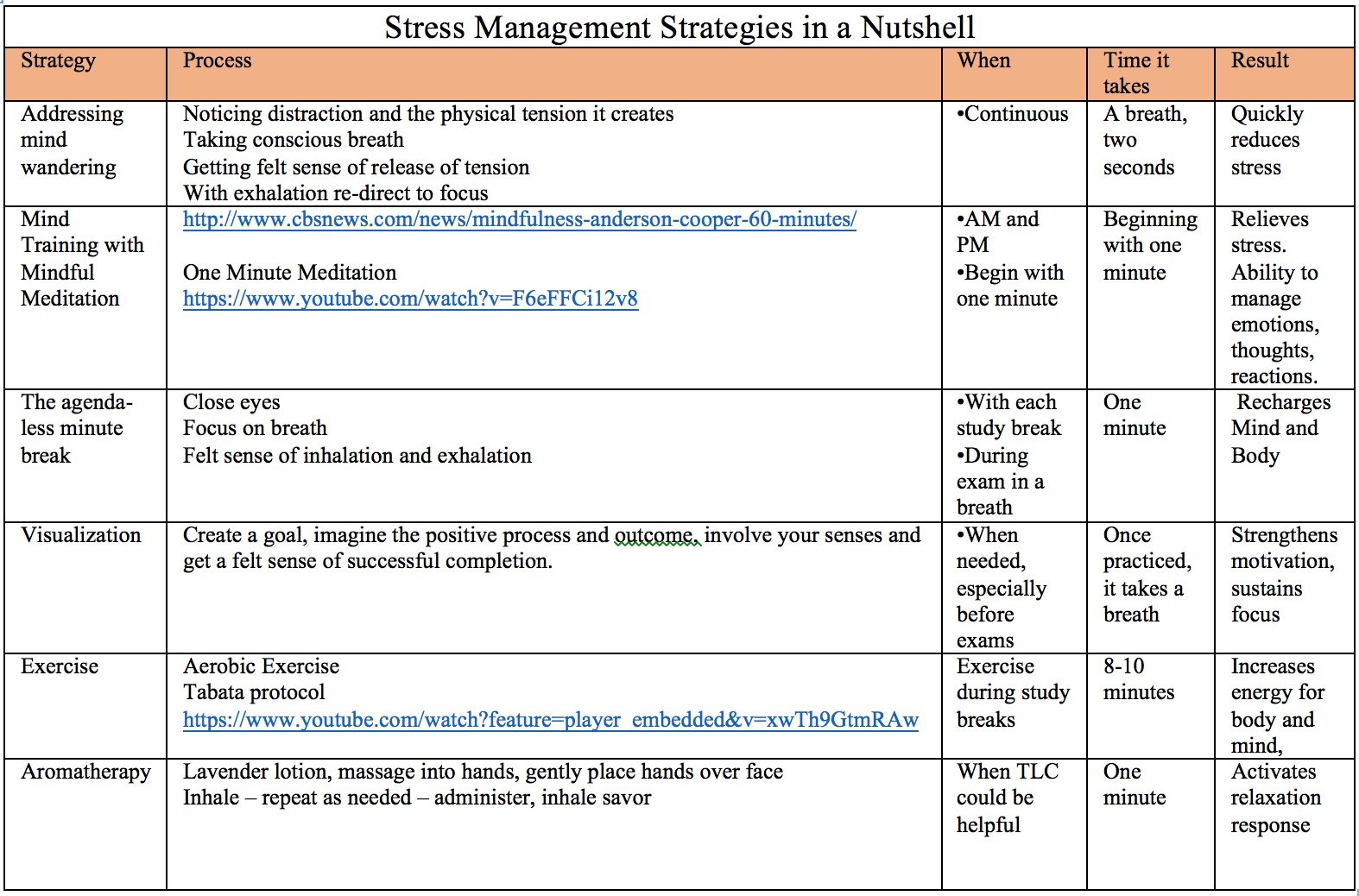

Following are the descriptions for three simple de-stressing strategies, which can be easily integrated into any schedule, no matter how busy.

Using the Breath–The Agenda-less Minute

The breath is a perfect tool to cultivate a state of mind which is curious, open and non-judging. You may want to try the following one minute exercise to refresh your brain periodically while you are studying:

For one minute, close your eyes and sit without an agenda. Get a felt sense of your body on the chair.

Stay in your body and gently re-direct your attention back to a “felt sense” of your body on the chair when attention wanders. Let go of judging. Keep your focus on noticing your breath, the felt sense of the breath touching the upper lip as you exhale and the inside of your nose as you inhale – just this. Notice how even in such a short amount of time you can gain a sense of grounding, relaxation and focus. If you are panicked, try to breathe in measured way: inhale to the count of 4, hold to the count of 6, exhale to the count of 8. A few of these will calm the amygdala and help you regain your equilibrium.

Visualization

Remember that you do not have to be able to actually picture or “see” anything in order to use visualization successfully. Getting the “felt sense” will do the trick. Stop studying for a minute, close your eyes, allow yourself to let go of tension in your body.

The Balloon Exercise: Imagine a balloon floating to the right of your face – imagine yourself writing the grade you are preparing for on it with day glow marker. Get a felt sense of the balloon next to you – whenever you become stressed, anxious, distracted, take a breath, look up to your right and focus on the number on the balloon. Use this exercise to keep your eyes on the prize and your study sessions effective and efficient.

Exercise

You may not be able to spend as much time at the gym as you would like, and yet knowing that aerobic exercise specifically helps cognition will help you make short study breaks work for you. Study in increments of 30/45 minutes, then take a short break – 5-8 minutes of aerobic exercise, running up and down stairs, jumping jacks, dancing your heart out for 5 minutes will help you stay fit in the long run and alert and awake for smarter study time. Unless your health prevents rigorous exercise, using the Tabata protocol, a high intensity training is an option as well, but only for the already fit and not-so-faint-of heart.

The goal of this short article is to allow the reader to pause and consider the efficacy of taking care of mind and body, a concept which at this time is not yet integrated in medical or undergraduate school curricula, but hopefully will be one day. In order to become the health practitioner the world needs, you have to model what you will expect from your future patients: to care for their own mental, physical and emotional health. Model now for yourself and your future patients what you know to be true: physician heal thyself.

Mind Training: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/mindfulness-anderson-cooper-60-minutes/

One Minute Meditation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6eFFCi12v8

Tabata Protocol: https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=xwTh9GtmRAw

Bibliography

- http://www.stress.org/stress-effects/ The American Institue of Stress

- http://www.helpguide.org/articles/stress/stress-symptoms-causes-and-effects.htm

- http://brainconnection.brainhq.com/2003/03/12/why-zebras-dont-get-ulcers/ Why Zebras don’t get ulcers

- http://www.evokelearning.ca/the-impact-of-stress-on-academic-success/ The effect of stress on academic success

- http://www.embodiment.org.uk/topics/felt_sense.htm Embodied Situated Cognition, The Felt Sense

- http://www.sonoma.edu/users/s/swijtink/teaching/philosophy_101/paper1/goleman.htm Daniel Goleman’s five components of emotional intelligence

- http://www.tabataprotocol.com/ Tabata Protocol