Last Updated on May 2, 2023 by Laura Turner

What changes are proposed to non-competes, how changes might affect physicians and other professionals, and what rules apply now

In recent years, policymakers have shown increasing interest in limiting or eliminating non-competition/restrictive covenant clauses (known widely as “non-competes”) in employment that prevent employees from freely moving from one job to another. State legislatures have led the effort, but, in many cases, the new laws they passed did not cover all of the workforce—often leaving undisturbed non-competes affecting higher wage-earners, including most, if not all, healthcare workers. In January 2023, the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) proposed a new federal regulation that would have the sweeping effect of banning nearly all non-competes across the country, including for doctors and other healthcare workers.

A non-compete clause is a contractually-binding promise by a worker not to work for or own a business that is engaged in essentially the same work they do for their present employer for some period of time after the employment relationship ends and in a prescribed geographic area. For example, if you work as a surgeon for ABC Hospital, a non-compete clause would provide that once you leave ABC Hospital, you cannot provide surgical services for another hospital or practice group within 20 miles for three years. Unless the new job would be greater than 20 miles away or you waited three years to take a job within the 20 miles, the non-compete clause would prohibit you from accepting the new job.

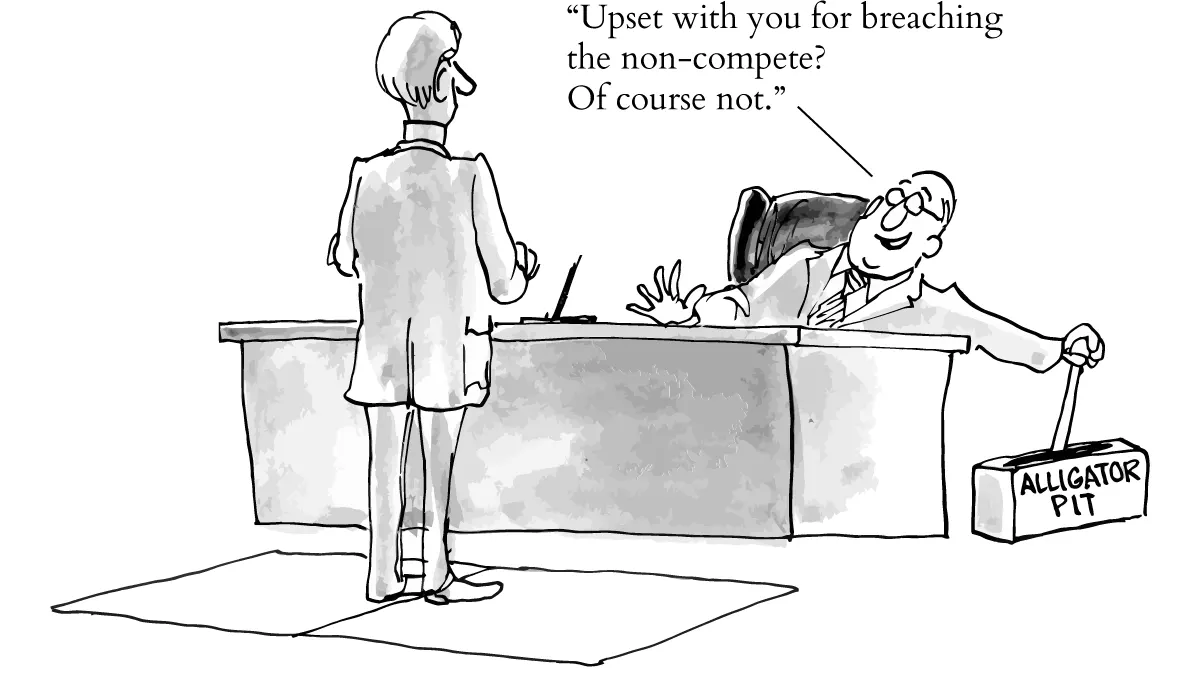

Many non-compete clauses can be enforced in court, including the former employer seeking an injunction to prevent you from working for the new employer or imposing liquidated damages (essentially a pre-set financial penalty). In some industries, including medicine, prospective employers may refuse even to consider applicants subject to a non-compete clause.

As a result, non-competes limit the job mobility of healthcare providers, which can prevent providers from seeking better career opportunities or more lucrative positions. In theory, medical residents and fellows training in ACGME-accredited programs should already be protected from non-competes by virtue of the ACGME’s Institutional Requirement IV.M. that says sponsoring institutions or programs cannot “require a resident/fellow to sign a non-competition guarantee or restrictive covenant.”

Learn more about physician contracts:

The FTC’s proposed ban on non-competes is premised on Sections 5 and 6(g) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which prohibits “unfair methods of competition” and empowers the agency to write regulations to enforce the Act. The FTC has concluded that non-compete clauses are an unfair method of competition in that, among other things, they restrict labor mobility and, thus, competition. The agency’s study shows that non-competes affect approximately 20% of workers (~30 million people) and cost them—even ones not restricted personally by such clauses—significant wage losses. The agency calculates that the new rule would increase wages by $250 to $296 billion annually. The agency also concluded that non-competes can prevent employers from obtaining the most qualified workers, which in turn adversely affects the quality of services they provide.

The scope and breadth of the FTC’s proposed rule is notable:

- The FTC proposal applies to all workers regardless of how much they are paid. This contrasts with many state law restrictions on non-competes that apply only up to a certain pay level. For example, in Maryland, the statutory limit on non-competes ushered in by the Noncompete and Conflict of Interest Clauses Act in 2019 nullifies non-competes only for employees who earn an amount equal to or less than $31,200 annually or $15.00 per hour. Other states like Colorado, Illinois, Maine, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia, and Washington have similar constructs but with a wide range of salary thresholds, some reaching up to $150,000. In the District of Columbia, “medical specialists” (i.e., those primarily providing medical services who hold a medical license, are physicians, have completed a residency, and are paid at least $250,000 annually) are excluded from the District’s non-compete protections.

- The FTC proposal applies to all workers and fields of work. Some states limit or prohibit non-competes only by certain classes of workers, like Rhode Island’s law that protects those earning wages at or below 250% of the federal poverty level, nonexempt workers, undergraduate or graduate students working while enrolled in school, and those under the age of 18. And court decisions in states like Maryland generally do not favor or disfavor non-competes in particular fields, even in the healthcare industry, where it might seem intuitive to prevent limits on the mobility of providers to work wherever their skills are needed.

The broad application of the FTC’s proposed ban means that a wide swath of higher wage earners, including doctors, tech workers, and executives, would now be protected. Indeed, the proposed rule extensively discussed non-competes’ effect on physicians and noted that a ban would elevate physician pay by a range of double-digit percentages, and lower patient costs.

Further, the FTC proposal would apply to existing non-competes. To comply with the regulation, employers would need to rescind existing non-competes within 180 days of the regulation becoming final, and notify workers (and former workers) of this within 45 days of the recission.

While that is a lot of good news for workers, the excitement should be tempered by several considerations.

First, the rule is merely a proposed change that must still be finalized after the notice-and-comment period. It is not unusual for proposed rules to wither on the vine and never emerge as final rules. However, this does seem to be a priority for President Biden, who issued an Executive Order calling for a ban, and FTC Chair Lina Khan, who is waging a public relations campaign (exemplified by this New York Times op-ed) in support of the rule.

Second, the FTC’s proposal would not affect non-disclosure agreements (promises not to divulge certain, usually proprietary, employer information) or non-solicitation agreements (promises not to attempt to draw clients or other employees away from the employer) in most cases.

Third, the proposal will not go into effect until 60 days after it is published as a final rule, and not be enforced for another 120 days after that. Because the rulemaking process can be quite lengthy, don’t expect any changes for quite some time. The FTC is accepting public comments on the proposed rule until March 10, 2023, and they can be submitted online. Some of the topics on which comment was requested, along with a number of alternative approaches described in the proposed rule, suggest that the ultimate product of the rulemaking may be less than a total ban.

Fourth, it is likely that opponents of the rule will mount legal challenges to it, which may at least delay implementation if not invalidate some or all of the rule. The FTC seems to have anticipated this and included a great deal of data and discussion in the proposed rule, amounting to 210 of the 216 pages in the notice of proposed rulemaking.

It will be interesting to see how this rule fares and what new state laws develop as the trend towards limiting non-competes continues.